- Oct 24, 2016

They said I was a witch.

What would they know?

I lived off the land, like anyone with any common sense to spare would have. I learned from the indigenous people which plants to harvest and which to avoid, and how to trap the wandering rabbit and track the wild deer. I gathered roots and berries in the woods, and I never went hungry, though there were some lean times. The others starved because they clung to old beliefs that didn’t fit the new world and refused to touch anything that came out of the forest. It wasn’t my fault they withered, but they blamed me for it.

I liked my solitude. I built my one-room home well outside the town, near the trees and the river that sustained me. I planted a modest garden of herbs and wildflowers and watched the bees and butterflies come. I had no need for town gossip or gatherings or Sunday school. To the townsfolk, this made me different — an outsider, though I’d traveled with them many months to this place and had known them all from birth.

I didn’t marry. There was no man with a claim on my heart, and why should I join myself to another for comfort or convenience? I needed no man to take care of me — I could do that myself. Somehow, this made me dangerous.

I was an unmarried woman of childbearing age, living alone near the woods, consorting with the natives and prospering while others went hungry. Of course they thought I was a witch.

Imbeciles.

Instead of seeking my help or heeding my advice, they shunned me. They whispered and talked. When I traveled into town to trade, I was refused. When I tried to bargain, I was turned away. When I walked down the dusty roads, mothers clutched their children, as if I would snatch the babes away and eat them on the spot.

I stopped going into town. It wasn’t worth the trouble. I could forage for what I needed, make my own or go without. I didn’t need the townsfolk, and they obviously didn’t need me.

But they couldn’t leave me alone.

I was happy. Content in my quiet life. That was perhaps the final straw for them.

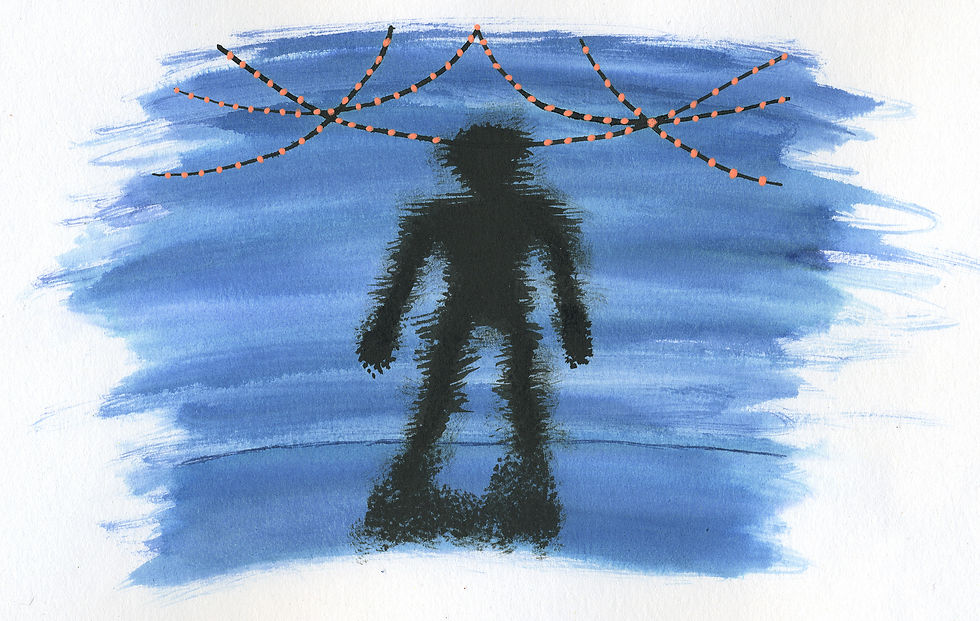

They came at night. There was a full moon rising over the treetops. I saw the line of bright orange torches marching down the hill to my home.

I knew what was coming. I knew what they whispered about me. Witch. There was only one way to deal with a witch.

I’m ashamed to say I ran. I sped into the woods, hoping to find sanctuary in the trees. But the townsfolk were more clever than I gave them credit for. They sent men ahead to surround my cabin. They were armed with clubs. They made sure I didn’t escape.

They caught me fleeing. They beat me, splintering bones and bruising flesh until I couldn’t run or stand or crawl, until all I could do was curl into a ball and wait for the next blow to fall.

Eventually, they stopped. I was surrounded by grim, dirty-faced peasants. I was forced to watch through bloodied eyes as they built my funeral pyre. I was lashed to a stake and ordered to confess to my imagined crimes as they held flames at my feet.

I stayed silent. I burned anyway.

They razed my land and tossed my charred corpse in the river. There was no bright light for me at my death — no door to take me to the next life. There was no peace for me. I lingered near the water, forgotten but not gone.

For years, no one came to my riverbank. Perhaps the townsfolk feared it after what they’d done. But when the black scars finally faded from the land, they wandered onto my property and into my water to swim and bath and drink.

One night, a man came under the light of the full moon. His face was familiar. I remember it contorted with hate as a heavy club reigned down blows upon me. Forgotten anger filled me. Why should this man enjoy life while I was trapped in unending death, chained to the world and unable to savor it?

He saw me on the riverbank. His eyes went wide and his face went pale as I stalked toward him. He fell backward into the river. The water swirled around my knees as I followed him and watched as the plants tangled around him and took him under. He didn’t come up again.

I’m not sorry for his death. Or the ones that followed.

There were many who came after that day. I let some of them pass unharmed — the ones who’d followed in fear, the ones who were, in the whole, not so bad.

Others fell to their watery deaths. The bullies, the scaremongers, the men who beat me. I didn’t get them all. There were too many of them for me to exact my revenge in a single generation.

The only good thing about being a ghost is that I have plenty of time. Maybe I didn’t get the man who lit the fire that night. But I took his grandson from him, a little bastard who wandered too close to my shores. My fingers wrapped around his throat as he thrashed in the watery weeds. Maybe I didn’t kill the woman who spat in my face as the flames took me. But I watched as the current dragged her beloved daughter away.

There are some who remain seared in my memory, men and women I haven’t punished yet, despite the many years I’ve haunted these banks. Their time will come. Sooner or later, someone with their blood and black hearts will appear, and I will have my retribution. Perhaps, when they’re all dead, I’ll no longer be trapped here, watching time slowly pass.

I’m not a witch. But I am a ghost. And sooner or later, they’ll all pay for that.